Identification. The name Germany is derived from the Latin word Germania, which, at the time of the Gallic War (58–51

B.C.E. ), was used by the Romans to designate various peoples occupying the region east of the Rhine. The German-language name Deutschland is derived from a Germanic root meaning

volk, or people. A document (written in Latin) from the Frankish court of 786

C.E. uses the term theodisca lingua to refer to the colloquial speech of those who spoke neither Latin nor early forms of Romance languages. From this point forward, the term

deutsch was employed to mark a difference in speech, which corresponded to political, geographic, and social distinctions as well. Since, however, the Frankish and Saxon kings of the early Middle Ages sought to characterize themselves as emperors of Rome, it does not seem valid to infer an incipient form of national consciousness. By the fifteenth century, the designation

Heiliges Römisches Reich ,or "Holy Roman Empire," was supplemented with the qualifying phrase

der deutschen Nation , meaning "of the German Nation." Still, it is important to note that, at that point in history, the phrase "German nation" referred only to the Estates of the Empire— dukes, counts, archbishops, electoral princes, and imperial cities—that were represented in the Imperial Diet. Nevertheless, this self-designation indicates the desire of the members of the Imperial Estates to distinguish themselves from the curia in Rome, with which they were embroiled in a number of political and financial conflicts.

The area that became known as Deutschland, or Germany, had been nominally under the rule of the German king—who was usually also the Roman emperor—since the tenth century. In fact, however, the various territories, principalities, counties, and cities enjoyed a large degree of autonomy and retained distinctive names and traditions, even after the founding of the nation-state—the

Kaiserreich or German Empire—in 1871. The names of older territories—such as Bavaria, Brandenburg, and Saxony—are still kept alive in the designations of some of today's federal states. Other older names, such as Swabia and Franconia, refer to "historical landscapes" within the modern federal states or straddling their boundaries. Regional identities such as these are of great significance for many Germans, though it is evident that they are often manipulated for political and commercial purposes as well.

The current German state, called the Federal Republic of Germany, was founded in 1949 in the wake of Germany's defeat in World War II. At first, it consisted only of so-called West Germany, that is the areas that were occupied by British, French, and American forces. In 1990, five new states, formed from the territories of East Germany—the former Soviet zone, which in 1949 became the German Democratic Republic (GDR)—were incorporated into the Federal Republic of Germany. Since that time, Germany has consisted of sixteen federal states: Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Berlin, Brandenburg, Bremen, Hamburg, Hesse, Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, Saarland, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Schleswig-Holstein, and Thuringia.

Location and Geography. Germany is located in north-central Europe. It shares boundaries with nine other countries: Denmark, Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands. At various

Germany

times in the past, the German Reich claimed bordering regions in France (Alsace-Lorraine) and had territories that now belong to Poland, Russia, and Lithuania (Pomerania, Silesia, and East Prussia). Shortly after the unification of East and West Germany in 1990, the Federal Republic signed a treaty with Poland, in which it renounced all claims to territories east of the boundary formed by the Oder and Neisse rivers—the de facto border since the end of World War II.

The northern part of Germany, which lies on the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, is a coastal plain of low elevation. In the east, this coastal plain extends southward for over 120 miles (200 kilometers), but, in the rest of the country, the central region is dotted with foothills. Thereafter, the elevation increases fairly steadily, culminating in the Black Forest in the southwest and the Bavarian Alps in the south. The Rhine, Weser, and Elbe rivers run toward the north or northwest, emptying into the North Sea. Similarly, the Oder river, which marks the border with Poland, flows northward into the Baltic Sea. The Danube has its source in the Black Forest then runs eastward, draining southern Germany and emptying eventually into the Black Sea. Germany has a temperate seasonal climate with moderate to heavy rainfall.

Demography. In accordance with modern European patterns of demographic development, Germany's population rose from about 25 million in 1815 to over 60 million in 1914, despite heavy emigration. The population continued to rise in the first half of this century, though this trend was hindered by heavy losses in the two world wars. In 1997, the total population of Germany was 82 million. Of this sum, nearly 67 million lived in former West Germany, and just over 15 million lived in former East Germany. In 1939, the year Germany invaded Poland, the population of what was to become West Germany was 43 million and the population of what was to become East Germany was almost 17 million. This means that from 1939 to 1997, both the total population and the population of West Germany have increased, while the population of East Germany has decreased.

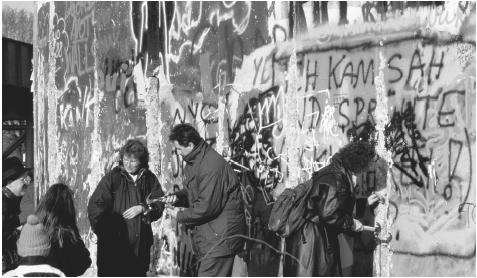

Following World War II, the population of both parts of Germany rose dramatically, due to the arrival of German refugees from the Soviet Union and from areas that are now part of Poland and the Czech Republic. In 1950, eight million refugees formed 16 percent of the West German population and over four million refugees formed 22 percent of the East German population. Between 1950 and 1961, however, more than 2.5 million Germans left the German Democratic Republic and went to the Federal Republic of Germany. The building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 effectively put an end to this German-German migration.

From 1945 to 1990, West Germany's population was further augmented by the arrival of nearly four million ethnic Germans, who immigrated from Poland, Romania, and the Soviet Union or its successor states. These so-called

Aussiedler or return settlers took advantage of a provision in the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany, which grants citizenship to ethnic Germans living outside of Germany.

Another boost to the population of West Germany has been provided by the so-called

Gastarbeiter (migrant or immigrant workers), mostly from Turkey, the Balkans, Italy, and Portugal. Between 1961 and 1997, over 23 million foreigners came to the Federal Republic of Germany; seventeen million of these, however, later returned to their home countries. The net gain in population for Germany was still well over 6 million, since those who remained in Germany often established families.

The population of Germany is distributed in small to medium-sized local administrative units, though, on the average, the settlements tend to be larger in West Germany. There are only three cities with a population of over 1 million: Berlin (3.4 million), Hamburg (1.7 million), and Munich (1.2 million). Cologne has just under 1 million inhabitants, while the next largest city, Frankfurt am Main, has a population of 650,000.

Linguistic Affiliation. In the early nineteenth century, language historians identified German as a member of the Germanic subfamily of the Indo-European family of languages. The major German dialect groups are High and Low German, the language varieties of the southern highlands and the northern lowlands. Low German dialects, in many ways similar to Dutch, were spoken around the mouth of the Rhine and on the northern coast but are now less widespread. High German dialects may be divided into Middle and Upper categories, which, again, correspond to geographical regions. The modern standard is descended largely from a synthetic form, which was developed in the emerging bureaucracy of the territorial state of Saxony and which combined properties of East Middle and East Upper High German. Religious reformer Martin Luther (1483–1546) helped popularize this variety by employing it in his very influential German translation of the Bible. The standard language was established in a series of steps, including the emergence of a national literary public in the eighteenth century, the improvement and extension of public education in the course of the nineteenth century, and political unification in the late nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, massive population movements have contributed to further dialect leveling. Nevertheless, some local and regional speech varieties have survived and/or reasserted themselves. Due to the presence of immigrants, a number of other languages are spoken in Germany as well, including Polish, Turkish, Serbo-Croatian, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Mongolian, and Vietnamese.

Symbolism. Any review of national symbols in Germany must take into account the clash of alternative symbols, which correspond either to different phases of a stormy history or to different aspects of a very complex whole. The eagle was depicted in the regalia of the Holy Roman Empire, but since Prussia's victory over Austria in 1866 and the exclusion of Austria from the German Reich in 1871, this symbol has been shared by two separate states, which were united only briefly from 1937 to 1945. Germany is the homeland of the Reformation, yet Martin Luther is a very contentious symbol, since 34 percent of all Germans are Roman Catholic. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, Germany became known as the land of

Dichter und Denker , that is, poets and philosophers, including such luminaries as Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottfried von Herder, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich von Schiller, and Wilhelm von Humboldt. In the latter nineteenth century this image was supplemented by that of the Prussian officer and the saber-rattling Kaiser.

Der deutsche Michel —which means, approximately, "Mike the German," named after the archangel Michael, the protector of Germany—was a simpleton with knee breeches and a sleeping cap, who had represented Germany in caricatures even before the nineteenth century. The national and democratic movement of the first half of the nineteenth century spawned a whole series of symbols, including especially the flag with the colors black, red, and gold, which were used for the national flag in the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and again in the Federal Republic of Germany (as of 1949). The national movement also found expression in a series of monuments scattered over the countryside. The National Socialists were especially concerned with creating new symbols and harnessing old ones for their purposes. In the Federal Republic of Germany, it is illegal to display the

Hakenkreuz or swastika, which was the central symbol of the Nazi movement and the central motif in the national flag in the Third Reich (1933–1945).

The official symbols of the Federal Republic of Germany are the eagle, on one hand, and the black, red, and gold flag of the democratic movement, on the other. In many ways, however, the capital city itself has served as a symbol of the Federal Republic, be it Bonn, a small, relatively cosy Rhenish city (capital from 1949 to 1990), or Berlin, Germany's largest city and the capital of Brandenburg-Prussia, the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich, and, since 1990, the Federal Republic. From the

Siegessäule (Victory Column) to the

Reichstag (parliament), from the Charlottenburg Palace to the former Gestapo Headquarters, from the Memorial Church to the fragmentary remnants of the Berlin

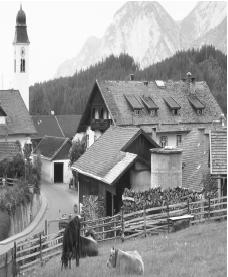

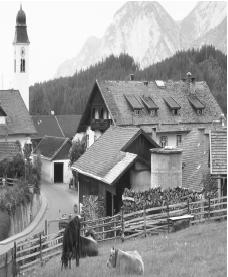

A Bavarian town settlement. Predominantly Catholic, Bavaria is home to many shrines and chapels, as well as the majestic Bavarian Alps.

Wall, Berlin contains numerous symbols of Germany and German history.

Given the contentious character of political symbols in Germany, many Germans seem to identify more closely with typical landscapes. Paintings or photographs of Alpine peaks and valleys are found in homes throughout Germany. Often, however, even features of the natural environment become politicized, as was the case with the Rhine during Germany's conflicts with France in the nineteenth century. Alternatively, corporate products and consumer goods also serve as national symbols. This is certainly the case with a series of high-quality German automobiles, such as Porsche, Mercedes-Benz, and BMW.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The emergence of the nation has been understood in very different ways at different times. Humanist scholars of the early sixteenth century initiated a discourse about the German nation by identifying contemporaneous populations as descendants of ancient Germanic peoples, as they were represented in the writings of Roman authors such as Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.E. ) and Cornelius Tacitus (c. 55–c.116 C.E. ), author of the famous work Germania. From the viewpoint of Ulrich von Hutten (1488–1523), among others, Tacitus provided insight into the origins and character of a virtuous nation that was in many ways equal or superior to Rome. The German humanists found their hero in Armin, or Hermann, who defeated the Romans in the battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 C.E.

The interest of German intellectuals in their ancient predecessors, as depicted in the literature of classical antiquity, continued into the eighteenth century, when it inspired the patriotic poetry of Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724–1803) and of the members of a group of poets called the Göttinger Hain , founded in 1772. The twentieth century scholar, Norbert Elias, has shown that the attention that bourgeois Germans of the eighteenth century devoted to the origins and the virtuous character of their nation was motivated in large part by their rejection of powerful aristocrats and courtiers, who modeled themselves on French counterparts.

On the eve of the French Revolution (1789), Germany was divided into nearly three hundred separate political entities of various sizes and with various degrees of sovereignty within the Holy Roman Empire. By 1794, French troops had taken the west bank of the Rhine, which had previously been divided among many different principalities; by 1806, Napoléon Bonaparte (1769–1821) had disbanded the Holy Roman Empire. In the same year, Napoléon's armies defeated Prussia and its allies in the simultaneous battles of Jena and Auerstädt. In its modern form, German nationalism took shape in response to this defeat. In the War of Liberation (1813–1815), in which many patriots participated as volunteers, the allied forces under Prussian leadership were successful in expelling the French from Germany. After the Congress of Vienna (1815), however, those who had hoped for the founding of a German nation-state were disappointed, as the dynastic rulers of the German territories reasserted their political authority.

With the rise of historical scholarship in the first half of the nineteenth century, the earlier emphasis on German antiquity was supplemented by representations of the medieval origins of the German nation. In the age of nationalism, when the nation-state was understood as the end point of a law-like historical development, German historians sought to explain why Germany, in contrast to France and England, was still divided. They believed that they had discovered the answer to this puzzle in the history of the medieval Reich. Shortly after the death of Charlemagne (814), the Carolingian empire split into a western, a middle, and an eastern kingdom. In the teleological view of the nineteenth century historians, the western kingdom became France and the eastern kingdom was destined to become Germany; the middle kingdom was subdivided and remained a bone of contention between the two emerging nations. The tenth century German king, Otto I, led a series of expeditions to Rome and was crowned as emperor by the pope in 962. From this point forward, Germany and the medieval version of the Roman Empire were linked.

German historians of the nineteenth century interpreted the medieval Reich as the beginning of a process that should have led to the founding of a German nation-state. The medieval emperor was viewed as the major proponent of this national development, but modern historians often criticized the actual behavior of the emperors as being inconsistent with national aims. The main villains of medieval history, at least in the eyes of latter-day historians—especially Protestants—were the various popes and those German princes who allied themselves with the popes against the emperor for reasons that were deemed to be "egotistical." This opposition of the pope and the princes was thought to have stifled the proper development of the German nation. The high point in this development was, the nationalist historians believed, the era of the Hohenstaufen emperors (1138–1254). The Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick I was rendered in nineteenth century historiography as a great hero of the German cause. After his reign, however, the empire suffered a series of setbacks and entered into a long period of decline. The early Habsburgs offered some hope to latter-day historians, but their successors were thought to have pursued purely dynastic interests. The low point in the national saga came in the Thirty Years War (1618–1648), when foreign and domestic enemies ravaged Germany.

Among the educated bourgeoisie and the popular classes of nineteenth century Germany, the desire for a renewal of the German Reich was widespread; but there was much disagreement about exactly how this new state should be structured. The main conflict was between those favoring a grossdeutsch solution to German unification, that is, a "large Germany" under Austrian leadership, and those favoring a kleindeutsch solution, that is, a "small Germany" under Prussian leadership and excluding Austria. The second option was realized after Prussia won a series of wars, defeating Denmark in 1864, Austria in 1866, and France in 1871. In the writings of the Prussian school of national history, Prussia's victory and the founding of the German Reich in 1871 were depicted as the realization of the plans of the medieval emperor, Frederick I. After the founding of the Reich, Germany pursued expansionist policies, both overseas and in the territories on its eastern border. Defeat in World War I led to widespread resentment against the conditions of the Versailles Treaty, which many Germans thought to be unfair, and against the founders of the Weimar Republic, who many Germans viewed as traitors or collaborators. Adolf Hitler, the leader of the National Socialist (Nazi) movement, was able to exploit popular resentment and widespread desires for national greatness. National Socialist propagandists built upon beliefs in the antiquity and continuity of the German nation, augmenting them with racialist theories, which attributed to the Germans a biological superiority over other peoples.

National Identity. Following World War II, German national identity became problematic, since the national movement seemed to have culminated in the Third Reich and found its most extreme expression in the murder of millions of people, including six million Jews. All further reflection on the German nation had to come to grips with this issue in one way or another. There have been many different attempts to explain Nazism and its crimes. Some see Adolf Hitler and his cronies as villains who misled the German people. Others blame Nazism on a flaw in the German national character. Still others see the beginning of Germany's problems in the rejection of the rational and universal principles of the Enlightenment and the adoption of romantic irrationalism. Marxist scholars see Nazism as a form of fascism, which they describe as the form that capitalism takes under certain historical conditions. Finally, some cite the failure of the bourgeois revolution in the nineteenth century and the lingering power of feudal elites as the main cause. Interpretations of this sort fall under the general heading of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or coming to terms with the past. Since the fall of the GDR, West German traditions of coming to terms with the past have been extended to the period of socialist rule in East Germany. Some Germans emphasize the similarities between the two forms of dictatorship, National Socialist and communist, while others, especially many East Germans, view the Third Reich and the GDR as being essentially dissimilar. Lingering differences between the attitudes and practices of West and East Germans are often attributed to the so-called Mauer in den Köpfen, or wall in the mind— an allusion to the physical wall that used to divide East and West Germany.

In recent years, German nationalism has been reexamined in accordance with views of the nation as an "imagined community" which is based on "invented traditions." Most scholars have concentrated on the organization, the symbolism, and the discourse of the national movement as it developed in the nineteenth century. The most significant contributions to the imagination and the invention of the German nation in this era took place in the context of (1) a set of typical voluntary associations, which supposedly harkened back to old local, regional, or national traditions; (2) the series of monuments erected by state governments, by towns and cities, and by citizens' groups throughout Germany; and (3) the various representations of history, some of which have been alluded to above. In addition, there is a growing body of literature that examines understandings of the nation and the politics of nationhood in the eighteenth century. There is much disagreement on the political implications of the critical history of nationalism in Germany. Some scholars seem to want to exorcize the deviant aspects of modern German nationalism, while retaining those aspects, with which, in their view, German citizens should identify. Others see nationalism as an especially dangerous stage in a developmental process, which Germans, in their journey toward a postnational society, should leave behind.

Ethnic Relations. The framers of the Grundgesetz (Basic Law or Constitution) of the Federal Republic of Germany adopted older laws that define citizenship according to the principle of jus sanguinis, that is birth to German parents (literally, law of blood). For this reason, many people born outside of Germany are considered to be German, while many people born in Germany are not. Since the 1960s, the country has admitted millions of migrant workers, who have, in fact, played an indispensable role in the economy. Although migrant workers from Turkey, Yugoslavia, Italy, Greece, Spain, and Portugal were called Gastarbeiter (literally, guest workers), many stayed in Germany and established families. They form communities, which are to varying degrees assimilated to German lifestyles. Indeed, many of the children and grandchildren of immigrant laborers regard themselves not as Turkish, Greek, or Portuguese, but as German. Nevertheless, they have had great difficulty in gaining German citizenship; and many Germans view them as Ausländer, or foreigners. Beginning in the year 2000, new laws granted restricted rights of dual citizenship to children of foreign descent who are born in Germany. This new legislation has been accompanied by intensified discussion about Germany's status as a land of immigration. All major political parties now agree that Germany is and should be a land of immigration, but they differ on many aspects of immigration policy.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

The earliest urban centers in what is now Germany were established by the Romans on or near the Rhine, often on the sites of pre-Roman settlements. Examples include Mainz, Trier, and Cologne. In the Middle Ages, older and newly founded towns became centers for commerce and for the manual trades, which were organized in guilds. Towns developed distinctive forms of social organization and culture, which set them off from the agrarian world of peasants and nobles. Some, called "free imperial cities," enjoyed the protection of the emperor and concomitant political and economic privileges. Others were directly subordinate to territorial lords, but still tried to gain or maintain a degree of autonomy.

By the early modern period, the most important commercial centers were the Hanseatic towns or cities of the northern coastal regions, the Rhenish towns, and the southern German towns, such as Augsburg, Würzburg, Regensburg, and Nuremberg, which were located along trade routes leading to the Mediterranean. There was often a sharp distinction between commercial cities, such as Leipzig, and court cities, such as Dresden. Up until the nineteenth century, however, the urban populations were very modest in size. In 1800, only Berlin and Hamburg had more than 100,000 inhabitants.

In the course of the nineteenth century, Germany experienced the forms of internal migration and urbanization that are typical of the transition from an agrarian to an industrial society. Industrial centers such as Leipzig, Berlin, and the Ruhr Valley grew dramatically in the second half of the century. Essen, in the Ruhr Valley, had 10,000 inhabitants in 1851 and 230,000 in 1905. The inadequate living conditions in the burgeoning cities were a major impetus for the workers' movement, which led to the formation of unions and working-class parties, most notably the Social Democratic and Communist parties.

German cities typically bear witness to all eras in the architectural history of Europe. The sequence of Romanic, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque styles is especially evident in churches, many of which have been renovated repeatedly over the centuries. Much of the urban architecture in Germany bears witness to the tastes of the nineteenth century, including the classicism of the first half of the century and the historicism (including neo-Gothic and neo-Renaissance) of the second half of the century. In the period of rapid industrial growth in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many German cities were largely rebuilt in the styles of the so-called

Gründerzeit, that is, the founding years of the new German Empire. Most cities dispensed of their medieval walls in the nineteenth century, but they retained their central town square, which is typically flanked by the town hall and sometimes the town church as well. In German cities today, some of the old town halls are still administrative centers, but others have become historical museums. The town square is, however, still used for festivals, weekly farmers' markets, and other special events. Since the late 1970s, inner city areas surrounding the central squares have often been transformed into pedestrian zones, with many shops, cafés, restaurants, and bars.

German cities experienced an unprecedented degree of destruction in the late years of World War II. In the first decades of the postwar era, they were often rebuilt in a modern style that differed sharply from the earlier appearance of the cities. Since the 1970s, cultural preservation has become a higher priority. This emphasis on the preservation of historic aspects of the city corresponds to an increased popular interest in all things historical and to the importance of the international tourist trade. The politics of cultural preservation is characterized by debates over the way in which the past should be represented in urban places. This applies especially to the representation of the Third Reich and World War II. In Berlin, for example, many buildings have been linked to different regimes of the past, including Brandenburg-Prussia, the German Empire, and the Third Reich. The Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, which was largely destroyed in the last war, has been left in ruins. It now serves as a memorial not to Kaiser Wilhelm but to World War II. In Dresden, the federal state of Saxony, the city of Dresden, and various citizens organizations have elected to rebuild the famous Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady), which was destroyed in the bombing of February 1945. Thus, they have chosen to emphasize the baroque tradition of "Florence on the Elbe," as Dresden was called. At the same time, Dresden—like many other towns and cities of former East Germany—has elected to remove many, though not all, of the monuments of the German Democratic Republic.

People socializing at a festival in Allgau. German beer, a favorite beverage, must be made only of water, hops, and malt.

Food and Economy

Read more about the

Food and Cuisine of Germany.

Food in Daily Life. Eating habits in Germany vary by social class and milieu, but it is possible to generalize about the behavior of the inclusive middle class, which has emerged in the prosperous postwar era. Most Germans acquire food from both supermarkets and specialty shops, such as bakeries and butcher shops. Bread is the main food at both breakfast and supper. Breakfast usually includes

brötchen, or rolls of various kinds, while supper— called

Abendbrot —often consists of bread, sausages or cold cuts, cheese, and, perhaps, a salad or vegetable garnish. The warm meal of the day is still often eaten at noon, though modern work routines seem to encourage assimilation to American patterns. Pork is the most commonly consumed meat, though various sorts of

wurst, or sausage, are often eaten in lieu of meat. Cabbage, beets, and turnips are indigenous vegetables, which are, however, often supplemented with more exotic fare. Since its introduction in the seventeenth century, the potato has won a firm place in German cuisine. Favorite alcoholic beverages are beer, brandy, and schnapps. German beers, including varieties such as

Pilsner, Weizenbier, and

Alt, are brewed according to the

deutsche Reinheitsgebot, i.e., the German law of purity from the sixteenth century, which states that the only admissible ingredients are water, hops, and malt. Large family meals are still common at noontime on Saturdays and Sundays. These are often followed in mid-afternoon by

Kaffee und Kuchen, the German version of tea time.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Special meals usually include meat, fish, or fowl, along with one of a number of starchy foods, which vary by region. Examples of the latter include

klöße (potato dumplings),

knödel (a breadlike dumpling), and

spätzle (a kind of pasta). Alternatively, Germans often celebrate in restaurants, which often feature cuisines of other nations. Greek restaurants tend to be more moderately priced, French restaurants are often more expensive, and the especially popular Italian restaurants span the range of price categories. The most important holiday meal is Christmas dinner. Regional and family traditions vary, but this often consists of goose, duck, or turkey, supplemented by red cabbage and potatoes or potato dumplings.

Basic Economy. Since the late nineteenth century, the German economy has been shaped by industrial production, international trade, and the rise of consumer culture. Consequently, the number of people involved in agricultural production has steadily declined. At the end of the twentieth century, only 2.7 percent of the German workforce was involved in agriculture, forestry, and fishery combined. Nevertheless, 48 percent of the total area of Germany was devoted to agriculture, and agricultural products covered 85 percent of domestic food needs.

Land Tenure and Property. The reform of feudal land tenure was not initiated in Germany until the period of upheaval and change during or following the Napoleonic Wars. In the various German states of those days, land reform was typically part of a broader reform plan that affected many aspects of political, economic, and social life. Programs for land reform, which were begun in the first decades of the nineteenth century, often were not completed until the second half of the century. Subsequently, however, new technologies and new organizational forms allowed agriculture to become an increasingly efficient branch of the modern economy. As the nineteenth century progressed, production rose dramatically. Simultaneously, the workforce shifted away from agriculture and into industry.

Following World War II, agricultural production was subject to further modernization, which resulted in fewer farmers on fewer farms of greater size. Nevertheless, the family farms of West Germany were on the average relatively small, the great majority having less than 100 acres (40 hectares). In East Germany, the postwar reform of agriculture was planned and executed by the state and the ruling socialist party. The most important aspects of this reform were the redistribution of land in 1945, the formation of agricultural collectives between 1952 and 1960, and the regional cooperation among different local collectives in the late 1960s and 1970s. This led to the creation of large, industrialized, cooperative farms. At the end of the Cold War (1989), however, over 10 percent of the East German population was involved in agricultural production, while West German farmers and farm workers made up only 5 percent of the population. After the reunification of Germany in 1990, agriculture in eastern territories was privatized.

The Federal Republic of Germany has liberal property laws which guarantee the right to private property. This right is, however, subject to a number of restrictions, especially with regard to state prerogatives concerning public utilities, public construction projects, mining rights, cultural preservation, antitrust issues, public safety, and issues of national security, to name only a few. Following the German reunification, there were a number of property issues to be resolved, since the GDR had expropriated private property and had not taken appropriate action with regard to private property expropriated during the Third Reich. The farmland taken from landowners between 1945 and 1949 was explicitly excluded from the reunification treaty; otherwise, it was required that expropriated property be restored to private owners. The ruling principle in this process was "restitution over compensation." The restitution of real estate was complicated by multiple claims on single objects. In agriculture, ownership issues were usually clear, since the land exploited by the cooperatives had remained in private hands. Since, however, the cooperatives had worked the land for over thirty years, building roads and buildings irrespective of property boundaries, private owners faced many practical difficulties in gaining access to their land.

Commercial Activities. In Germany, there is a strong tradition of

handwerk, or manual trades. In the manual trades, training, qualification, and licensing are regulated by special ordinances. Training and qualification occur through vocational schools and internships. These are an integral part of the modern educational system, though some of the vocabulary is reminiscent of guilds, which were abolished in the nineteenth century. For example, the owner or manager of a business enterprise in the manual trades is required to have his or her

Meisterbrief (master craftsman's certificate). In the mid-1990s, the eleven most important manual trades, in terms of both the number of firms and the total number of employees, were those of barbers and hairdressers, electricians, automobile mechanics, carpenters, housepainters, masons, metalworkers, plumbers, bakers, butchers, and building- and window-cleaners.

Major Industries. Among the industrial countries of Europe, Germany was a late comer, retaining a largely agricultural orientation until the later nineteenth century. Following German unification in 1871, rapid industrial development exploited extensive coal resources in the Ruhr Valley, in the Saarland, in areas surrounding Leipzig, and in Lusatia. Building upon a strong tradition of manual trades, Germany became a leader in steel production and metalworking. Coal reserves also provided the basis for an emerging carbo-chemical industry. When, in the decades following World War II, heavy industry migrated to sites in Asia and Latin America, Germany experienced a dramatic decrease in the number of industrial jobs; this was accompanied by the growth of the service sector (including retail, credit, insurance, the professions, and tourism). At the beginning of the 1970s, over half of the workforce was employed in industry; by 1998, however, this number had dwindled to less than one third. In the early twenty-first century, the most important industries in Germany are automobile manufacturing and the production of automobile parts, the machine industry, the metal products industry, the production of electrical appliances, the chemical industry, the plastics industry, and food processing.

Trade. After the United States, Germany has the second largest export economy in the world. In 1998, export accounted for 25 percent of the gross domestic product and import for nearly 22 percent. Export goods include products from the major industries cited above. Other than coal, Germany lacks fossil fuels, especially oil and natural gas. These products must be imported. Germany's most important trading partners are France, the United States, the United Kingdom, and other European lands. It also trades actively with East Asian countries and has become increasingly involved in eastern Europe.

Division of Labor. The work force in Germany includes laborers, entrepreneurs, employees and clerical workers, managers and administrators, and members of the various professions. Access to particular occupations is determined by a number of factors, including family background, individual ability, and education or training. Laborers in Germany are usually highly skilled, having completed vocational training programs. Beginning in the 1960s, the ranks of the laboring class were augmented by migrant workers from Turkey and other countries bordering on the Mediterranean. Both laborers and employees are represented by well organized and aggressive unions, which, in the postwar era, have often cooperated with entrepreneurial organizations and the state in long range economic planning. Since the 1970s, rising labor costs and the globalization of industrial production have led to high rates of unemployment, especially in areas where heavy industry was dominant, as in Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia. The problem of unemployment in the Federal Republic of Germany was exacerbated by the entry of the five new federal states of the former GDR in 1990. Once the Iron Curtain fell, East Germany lost its protected markets in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. As a result, its industry collapsed and hundreds of thousands lost their jobs. In 1998, unemployment rates were over 10 percent in former West Germany and 20 percent in former East Germany. The figures for the latter, however, did not take into account those who were involved in make-work and reeducation programs. Since many were pessimistic about the possibility of creating new jobs in eastern Germany, the flow of migrants to western Germany continued to the early twenty-first century.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. By the early twentieth century, German society was divided into more or less clear-cut classes. Industrial workers included both the skilled and the unskilled. The former came from the manual trades but became factory laborers when it had proved impossible or undesirable to remain independent. The middle classes included small businessmen and independent members of the trades, white-collar employees, professionals, and civil servants. Finally, the upper or upper middle classes consisted of industrialists, financiers, high government officials, and large landowners, among others. Members of these classes were usually associated with corresponding political organizations and milieus, for example, the workers with unions and socialist or communist organizations, and the middle classes with a range of bourgeois parties, occupational organizations, and patriotic societies. In the German Empire and the Weimar Republic, however, many Catholics of all classes were organized in the

Zentrum, or Center Party.

The National Socialist (Nazi) Party found supporters among all social classes, especially the middle classes. The Third Reich was, in many ways, an upwardly mobile society, which created new jobs, provided subsidies, and opened career opportunities for party members. The success of many party supporters was gained at the expense of members of the workers' movement and the Jews and other minorities.

In the prosperous West German society of the postwar era, class boundaries seemed to open up and admit more members into a new, more inclusive middle class. Correspondingly, the political distinction between the bourgeois and the socialist parties lessened. In East Germany, the Socialist Unity Party wanted to eliminate the bourgeoisie, which had compromised itself through its support of National Socialism. This was to be achieved by nationalizing larger private enterprises, forcing independent farmers to enter agricultural cooperatives, and favoring the children of workers in education and hiring programs. The GDR described itself as a "workers' and peasants' state," but some social scientists have described it as a leveled middle-class

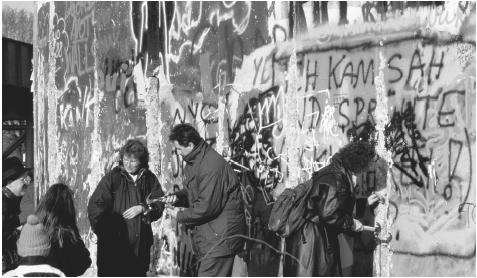

People collecting pieces of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Built in 1961, the wall was a visible reminder of Germany's defeat in World War II and subsequent division into first four, then two distinct and independent zones.

society, made up of skilled workers, employees, and specialists, who held state-subsidized positions. Since the entry of the five new federal states into the Federal Republic, class relations have been reshuffled in eastern Germany once again, sending many westward in search of work and bringing many eastward to occupy leading positions in government and corporations. Large groups of retired and unemployed persons live side by side with entrepreneurs, managers, employees, civil servants, and others working in the service sector.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Social class in Germany is not only a matter of training, employment, and income but also a style of life, self-understanding, and self-display. The so-called

bildungsbürgertum, or educated bourgeoisie of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to cite one example, was characterized first and foremost by a particular constellation of artistic and literary taste, habits, and cultural and ethical values. Modern sociologists have tended to focus on the full range of social milieus that make up German society and on the various kinds of consumer behavior that characterize each milieu. Thus, variations in interior design in private residences, eating habits, taste in music and in other entertainment forms, reading materials, personal hygiene and clothing, sexual behavior, and leisure activities can all be viewed as indexes of association with one of a finite set of social milieus. A single example must suffice. Highly educated persons in business, government, or the professions are likely to read the

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (a major newspaper, published in Frankfurt), if they are relatively conservative, or the

Süddeutsche Zeitung or the

Frankfurter Rundschau (newspapers published in Munich and Frankfurt, respectively), if they are somewhat left of center. Members of both groups will probably also read the politically moderate and rather sophisticated weekly newspaper,

Die Zeit (Hamburg). Conservatives who are more interested in politics and business than in arts and literature may read

Die Welt (another Hamburg newspaper), while readers who identify more closely with an alternative leftist milieu are more likely to reach for

die tageszeitung, or

taz (a newspaper published in Berlin). In contrast, those with a vocational education, who are small business owners, employees, or workers may read the very popular

Bild (Hamburg), a daily tabloid newspaper. Finally, those who still feel loyal to the defunct GDR or who hope that socialism will come again often read

Neues Deutschland (Berlin), which was the official organ of the Socialist Unity Party, that is the East German communist party.

Political Life

Government. Germany is a parliamentary democracy, where public authority is divided among federal, state, and local levels of government. In federal elections held every four years, all citizens who are eighteen years of age or older are entitled to cast votes for candidates and parties, which form the Bundestag, or parliament, on the basis of vote distribution. The majority party or coalition then elects the head of the government—the Kanzler (chancellor)—who appoints the heads of the various government departments. Similarly, states and local communities elect parliaments or councils and executives to govern in their constitutionally guaranteed spheres. Each state government appoints three to five representatives to serve on the Bundesrat, or federal council, an upper house that must approve all legislation affecting the states.

Leadership and Political Officials. Germany's most important political parties are the Christian Democratic Union and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union; the Social Democratic Party; the Free Democratic or Liberal Party; The Greens; and the Party of Democratic Socialism, the successor to the East German Socialist Unity Party. In 1993, the Greens merged with a party that originated in the East German citizens' movement, called Alliance 90. Since the late 1980s, various right-wing parties have occasionally received enough votes (at least 5 percent of the total) to gain seats in some of the regional parliaments. The growth of right wing parties is a result of political agitation, economic difficulties, and public concern over the increasing rate of immigration. The first free all-German national election since 1932 was held on 2 December 1990 and resulted in the confirmation of the ruling Christian Democratic/Free Democratic coalition, headed by Helmut Kohl, who was first elected in 1982. The Christian Democrats won again in 1994, but in the election of 1998, they were ousted by the Social Democrats, who formed a coalition government with Alliance 90 (the Greens). Like his then counterparts in the United States and Great Britain, Gerhard Schröder, the chancellor elected in 1998, described himself as the champion of the new political "middle."

Social Problems and Control. In the Federal Republic of Germany, police forces are authorized by the Departments of Interior of the sixteen federal states. Their activities are supplemented by the Bundesgrenzschutz (Federal Border Police) and the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution). In the early twenty-first century, organized crime and violence by right-wing groups constituted the most serious domestic dangers.

Military Activity. The German armed forces are under the control of the civilian government and are integrated into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). German men who are eighteen years of age are required to serve for ten to twelve months in the armed forces—or an equivalent length of time in volunteer civilian service. In 2000, Germans began a public debate about the restructuring of the armed forces.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Germany's social welfare programs are among the oldest of any modern state. In 1881, the newly founded German Reich passed legislation for health insurance, accident insurance, and for invalid and retirement benefits. The obligation of the state to provide for the social welfare of its citizens was reinforced in the Basic Law of 1949. In the Federal Republic of Germany, the state supplements monthly payments made by citizens to health insurance, nursing care insurance, social security, and unemployment insurance. Beginning in the late twentieth century, questions were raised about the long-term viability of existing social welfare programs.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

German society is structured by many different

Verbände, or associations, which are often organized at federal, regional, and local levels. There are associations for business and industry, for workers and employees (unions), for social welfare, for environmental protection, and for a number of other causes or special interests. Through such associations, members seek to influence policy making or to act directly in order to bring about desired changes in society. Associations that contribute to public welfare typically operate according to the principle of subsidiarity. This means that the state recognizes their contribution and augments their budgets with subsidies.

In local communities in Germany, public life is often shaped to a large degree by

Vereine , or voluntary associations, in which citizens pursue common

People fill a street in Lindau. Since the late 1970s, many inner-city areas have become pedestrian zones.

interests or seek to achieve public goals on the basis of private initiative. Such organizations often provide the immediate context for group formation, sociability, and the local politics of reputation.

Beginning in the late twentieth century, German society was strongly affected by the so-called new social movements, which were typically concerned with such issues as social justice, the environment, and peaceful coexistence among neighboring states. In the last years of the GDR, several civil rights groups emerged throughout the country and helped usher in the

Wende (literally, turning or transition) in 1989 and 1990.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. With the transition from agricultural to industrial society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, women, who had been largely restricted to the domestic sphere, began to gain access to a wider range of economic roles. More than a century after this process began, women are represented all walks of life. Nevertheless, they are still more likely to be responsible for childcare and household management; and they are disproportionately represented among teachers, nurses, office workers, retail clerks, hair dressers, and building and window cleaners.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. The Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany states that men and women have equal rights under the law. Nevertheless, women did not enjoy juridical equality in marriage and the family until new family legislation was passed in 1977. Previously, family law, which had been influenced by the religious orientation of the Christian Democratic and Christian Social parties, had stated that women could seek outside employment only if this were consistent with their household duties. East German law had granted women equal rights in marriage, in the family, and in the workplace at a much earlier date. Needless to say, in both the Federal Republic and in the former GDR, the ideal of equality of opportunity for men and women was imperfectly realized. Even under conditions of full employment in East Germany, for example, women were under represented in leading positions in government, industry, and agricultural production.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. In Germany, the basic kinship group, as defined by law, is the nuclear family, consisting of opposite sex partners, usually married, and their children; and, in fact, the majority of households are made up of married couples with or without children. Between 1950 and 1997, however, there were fewer and fewer marriages both in total numbers and per capita. In 1950, there were a total of 750,000 marriages, or eleven marriages for every thousand persons; in 1997, by contrast, there were 423,000 marriages, or five marriages for every thousand persons. It is estimated that 35 percent of all marriages ended in divorce in the late twentieth century. In light of these facts, there has been much media speculation on the "crisis of the family," as has been the case in other industrial societies of western Europe and North America as well. Despite the increase in the number of unmarried couples, with or without children, such couples make up only 5 percent of all households. Nevertheless, the rising number of children who are born to unmarried mothers (currently 18 percent, lower than the European Union average), the rising divorce rate, and the growth of alternative forms of partnership have, since 1979, led to a broadening of the concept of family and a liberalization of family law and family policy.

Much more dramatic is the reduction of the birthrate. The annual number of deaths has been greater than the annual number of births since 1972. On the eve of reunification in 1990, there was an annual birthrate of 1,400 children per 1,000 women in West Germany and 1,500 children per 1,000 women in East Germany. In the new federal states of former East Germany, the birthrate had sunken to 1,039 children per 1,000 women by 1997. In both parts of Germany, the reduction of the birthrate is matched by a progressive reduction in the average size of households. In 1998, less than 5 percent of private households had five or more members. Since 1986, the Federal Republic of Germany has provided for the payment of Kindergeld (child-raising benefits) to families or single parents with children. As of January 1999, these payments were 250 marks (or approximately half that amount in dollars) per month for the first and second child up until his or her eighteenth birthday— and, in some cases, until the twenty-seventh birthday.

In the new federal states of former East Germany, there are fewer marriages and fewer children; but a disproportionately high number of children are born to unmarried couples. These differences between former East Germany and former West Germany may be attributed, in part, to the economic difficulties in the new federal states. Some of the differences, however, may be understood as lingering effects of the divergence of family law and social policy during the separation of the East and the West. In the GDR, the official policy of full employment for men and women was realized by providing women with benefits and services such as pregnancy leave, nursing leave, day-care centers, and kindergartens. In general, the family law of the GDR served to strengthen the position of women vis-á-vis men in their relationships to their children. With the cutback or elimination of such policies following the entry of the new federal states into the Federal Republic of Germany, there was both a greater hesitancy to have children and a greater tendency to view having children separately from marital status.

Kin Groups. A society the size of Germany lends itself to the statistical analysis of family relations. It is unfortunate, however, that official statistics direct attention so single-mindedly to the nuclear family or variations thereof (unmarried couples, single parents) and cause observers to overlook family ties with grandparents, grown siblings, cousins, and other consanguineal or affinal relatives. Nevertheless, it is clear that ties with more distant relatives are a vital part of kinship in Germany at the onset of the twenty-first century, as is especially evident on holidays, at key points in the lifecycle of individuals, and in large family projects such as moving.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. In Germany, infant care and child rearing correspond to typical western European and North American patterns. Childhood is viewed as a developmental stage in which the individual requires attention, instruction, affection, and a special range of consumer products. Child rearing is typically in the hands of the mother and father or the single parent, but here, especially, the importance of the extended family is evident. Variations in child rearing behavior by social class and social milieu are, however, less well studied than other aspects of adult behavior. In light of the critique of the "authoritarian personality" by the German sociologist Theodor Adorno and others, some middle-class parents have tried to practice an anti-authoritarian form of child rearing. Adorno and his colleagues thought that certain child rearing practices, especially strict and arbitrary discipline, encourage stereotypic thinking, submission to authority, and aggression against outsiders or deviants. In the past, they argued, the prevalence of such practices in Germany contributed to the success of National Socialism.

In most federal states, the school system divides pupils between vocational and university preparatory tracks. The vocational track includes nine years of school and further part-time vocational training, together with a paid or unpaid apprenticeship. The university preparatory track requires attendance of the humanistic

Gymnasium, beginning in the fifth year of school, and successful completion of the

Abitur, a university entrance examination.

Higher Education. Germany has many universities and technical colleges, almost all of which are self-administered institutions under the authority of the corresponding departments of the individual federal states. University study is still structured according to the humanistic ideals of the nineteenth century, which entrusts students with a great deal of independence. The assignment of grades, for example, is largely independent of class attendance. Grades are given for oral and written examinations, which are administered at the departmental level after the completion of the semester. Students of law and medicine begin with their chosen subject in the first year at the university and pursue relatively specialized courses of study. Admittance to popular

A cowherd leads cows down a rural road at Reit im Winkl, Germany. The cows wear flowered headdresses for an annual celebration.

major subjects is governed by the so-called

Numerus clausus, which restricts the number of students, usually according to scores on college entrance examinations. German students pay no admission fees and are supported with monthly allowances or loans from the state.

Etiquette

It has often been noted that German society retains a small town ethos, which arose in the early modern period under conditions of political and economic particularism. Indeed, many Germans adhere to standards of bürgerlichkeit, or civic morality, which lend a certain neatness and formality to behavior in everyday life. When entering a store, for example, one is not likely to be noticed, unless one announces oneself forcefully by saying, " guten Tag " (literally, "good day") or "hello." In former East Germany, it is still common for friends and acquaintances to shake hands when they see each other for the first time each day. West Germans consider it more modern and perhaps more American not to do so. In pronouns of direct address, one uses either the formal sie or the informal du. Colleagues in the workplace typically address each other as Sie or use a title and the family name, such as, Herr or Frau Doktor Schmidt.

Life in public does not seem to be the highest good for all Germans, as urban centers often appear to be abandoned on Saturday afternoons and Sundays. This is linked to the issue of the operating hours of shops, which has been debated in Germany since the mid-1970s. For different reasons, both the unions and the churches opposed extended operating hours, as do many citizens, who are critical of "consumer societies" or who prefer, on the weekends, to remain with their families or in their private gardens.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Germany was the homeland of the Protestant Reformation, but, in the politically fragmented Holy Roman Empire of the sixteenth century, many territories remained faithful to Roman Catholicism or reverted back to it, depending of the policy of the ruling house. Today, 34 percent of the population belongs to the Evangelical (Protestant) Church and a further 34 percent belongs to the Catholic Church. Many Germans have no religious affiliation. This is especially true of former East Germany, where, in 1989, the Evangelical Church had 4 million members (out of a total population of 16.5 million) and the Catholic Church had only 921,000 members. Since 1990, the Evangelical Church has lost even more members in the new federal states.

The Evangelical Church is a unified Protestant church, which combines Lutherans, Reformed Protestants, and United Protestants. Reformed Protestants adhere to a form of Calvinism, while United Protestants combine aspects of Lutheranism and Calvinism. Other Protestant denominations make up only a small fraction of the population. Most German Catholics live in the Rhineland or in southern Germany, whereas Protestants dominate in northern and central parts of the country.

In 1933, there were over 500,000 people of Jewish faith or Jewish heritage living within the boundaries of the German Reich. Between 1933 and 1945, German Jews, together with members of the far more numerous Jewish populations of eastern Europe, fell victim to the anti-Semitic and genocidal policies of the National Socialists. In 1997, there are an estimated sixty-seven thousand people of Jewish faith or heritage living in Germany. The largest Jewish congregations are in Frankfurt am Main and Berlin.

In the postwar era, migratory workers or immigrants from North Africa and western Asia established Islamic communities upon arriving in Germany. In 1987, there were an estimated 1.7 million Muslims living in West Germany.

Religious Practitioners. Religious practitioners in Germany include especially the Protestant or Catholic pfarrer (minister or priest). In local communities, the minister or priest belongs to the publicly acknowledged group of local notables, which also includes local governmental officials, school officials, and business leaders. Roman Catholic priests are, of course, local representatives of the international church hierarchy, which is centered in Rome. Protestant ministers represent Lutheran, Reformed, or United churches, which are organized at the level of the regional states. These state-level organizations belong, in turn, to the Evangelical Church of Germany.

Rituals and Holy Places. From the smallest village to the largest city, the local church dominates the central area of nearly every German settlement. German churches are often impressive architectural structures, which bear witness to centuries of growth and renovation. In predominantly Catholic areas, such as the Rhineland, Bavaria, and parts of Baden-Württemberg, the areas surrounding the towns and villages are typically strewn with shrines and chapels. The processions to these shrines, which were common until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, have now been largely discontinued.

Despite processes of secularization, which had became intensive by the early nineteenth century, churches retained their importance in public life. Beginning in the 1840s, there was a popular movement to complete the Cologne cathedral, which was begun in the Middle Ages but which remained a construction site for 400 years. With the support of the residents of Cologne, the Catholic Church, and the King of Prussia (who was a Protestant), work on the cathedral was begun in 1842 and completed in 1880. The character of the ceremonies and festivals that accompanied this process indicate that the Cologne Cathedral served not only as a church but also as a national monument. Similarly, the national assembly of 1848, in which elected representatives met to draft a constitution for a united Germany, took place in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt. (The national and constitutional movement failed when the Prussian king refused the imperial crown, which was offered to him by the representatives of the national assembly.) One of the centers of the popular movement that led to the fall of the GDR in 1989–1990 was the Nikolaikirche (St. Nicolas Church) in Leipzig.

Since the late nineteenth century, churches and other historical buildings in Germany have become the objects of Denkmalpflege (cultural preservation), which may be understood as one aspect of a broader culture of historical commemoration. Together with museums, historical monuments constitute a new set of special sites, which may be approached only with a correspondingly respectful attitude.

Graveyards and war memorials occupy a kind of middle ground between holy sites and historical monuments. All settlements in Germany have graveyards, which surviving family members visit on special holidays or on private anniversaries. War memorials from World War I are also ubiquitous. Monuments to World War II often have a very different character. For example, the concentration camp Buchenwald, near Weimar, has, since the early 1950s, served as a commemorative site, which is dedicated to the victims of the National Socialist regime.

Death and the Afterlife. Nearly 70 percent of Germans are members of a Christian church, and many of these share common Christian beliefs in himmel (heaven) and hölle (hell) as destinations of the soul after death. Many other Germans describe themselves as agnostics or atheists, in which case they view beliefs in an afterlife as either potentially misleading or false. Funerary rites involve either a church service or a civil ceremony, depending on the beliefs of the deceased and his or her survivors.

Medicine and Health Care

Germans were among the leaders in the development of both Western biomedicine and national health insurance. Biomedical health care in Germany is extensive and of high quality. In addition to having advanced medical technology, Germans also have a large number of medical doctors per capita. In 1970, there was one medical doctor for every 615 people, while in 1997, there was one medical doctor for every 290. Forty-one percent of doctors are in private practice, while 48 percent are in hospitals, and 12 percent are in civil service or in similar situations.

In medical research, there is an emphasis on the so-called zivilisationskrankheiten (diseases of the "civilized" lands), that is, heart disease and cancer. In 1997, heart disease caused 47 percent of all deaths in former West Germany and 52 percent of deaths in former East Germany. In the same year, cancer was responsible for 25 percent of all deaths in former West Germany and 23 percent of deaths in former East Germany.

Alongside biomedicine, there is a strong German tradition of naturopathic medicine, including especially water cures at spas of various kinds. Water cures have been opposed by some members of the German biomedical establishment but are still subsidized to some extent by statutory health insurance agencies.

Secular Celebrations

German holidays are those of the Roman calendar and the Christian liturgical year. Especially popular are Sylvester (New Year's), Karneval or Fastnacht (Mardi Gras), Ostern (Easter), Himmelfahrt (Ascension Day), Pfingsten (Pentecost), Advent, and Weihnachten (Christmas). The new national holiday is 3 October, the Tag der deutschen Einheit (Day of German Unity).

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. The arts in Germany are financed, in large measure, through subsidies from state and local government. Public theaters, for example,

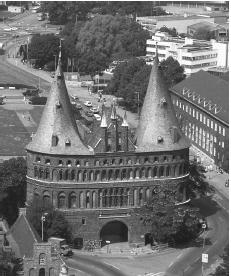

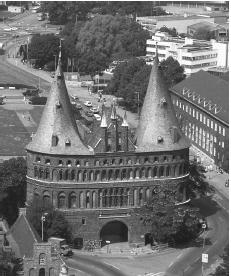

The Holstentor and Holsten gate, built between 1469 and 1478, in Lübeck, Germany.

gained 26 percent of their revenues from ticket sales in 1969–1970 but only 13.6 percent in 1996–1997. Public subsidies have been threatened in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries by budget cuts, which have been accompanied by calls for more sponsorship by private industry. In the new federal states of former East Germany, the once very dense network of theaters and concert halls has been reduced dramatically. In Saxony, for example, the

Kulturraumgesetz of 1994 (legislation for the creation of arts regions) requires neighboring communities to pool their resources, as, for example, when one community closes its concert hall but retains its theater, while another does just the opposite. Concert- or theatergoers are then required to travel about within the region, in order to take advantage of the full arts program. Still, many major and some minor German cities have excellent theater ensembles, ballets, and opera houses. Berlin and Munich are especially important centers for the performing arts.

Literature. Germany was a

Kulturnation, that is, a nation sharing a common language and literature, before it became a nation-state. As is well known, the printing press was invented by Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1400–1468) in Mainz about a half a century before the onset of the Protestant Reformation. The Luther Bible, written in the vernacular German of Upper Saxony, spread throughout the German-speaking world and helped to create a national reading public. This reading public emerged among the educated bourgeoisie in the Age of Enlightenment (eighteenth century). Important aspects of this public sphere were newspapers, literary journals, reading societies, and salons. The classical phase in the history of German literature, however, came during the transition from the Enlightenment to Romanticism, the two most important figures being Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) and Friedrich von Schiller (1759–1809). The nineteenth century saw a dramatic expansion of the publishing industry and the literary market and the blossoming of all modern literary genres. Following World War II, there was a split between the literary spheres of East and West Germany. German reunification began with an acrimonious debate over the value of East German literature.

Graphic Arts. German artists have contributed to every era in the history of the graphic arts, especially the Renaissance (Albrecht Dürer), Romanticism (Caspar David Friedrich), and Expressionism (the Brücke and the Blaue Reiter).

Performance Arts. Germans are especially well-known for their contributions in the area of classical music, and the heritage of great German or Austrian composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig von Beethoven, Johannes Brahms, Richard Wagner, and Gustav Mahler is still cultivated in concert halls throughout the country. Germans developed an innovative film industry in the Weimar Republic, but its greatest talents emigrated to the United States in the 1930s. In East Germany, Babelsberg was the home of DEFA (

Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft ), an accomplished film company. With the help of extensive public subsidies, a distinctive West German cinema emerged in the 1970s. Since then, however, attempts to reinvigorate the German film industry have proven difficult, in light of the popularity of products from Hollywood.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

In the course of the nineteenth century, German scientists and scholars cultivated distinct national traditions in the physical sciences, the humanities, and the social sciences, which served, in turn, as important models for other countries. Since the end of the World War II, however, science and scholarship in Germany have become internationalized to such a degree that it is problematic to speak of deutsche Wissenschaft (German Science), as was once common. The most important centers for science and scholarship in Germany today are the universities, independent research institutes, such as those sponsored by the Max Planck Society, and private industry.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor W., et al. The Authoritarian Personality, 1982.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Rev. Ed., 1991.

Beyme, Klaus von, Werner Durth, Niels Gutschow, Winfried Nerdinger, and Thomas Topfstedt, eds. Neue Städte aus Ruinen: Deutscher Städtebau der Nachkriegszeit, 1992.

Blackbourn, David. The Long Nineteenth Century: A History of Germany, 1780–1918, 1998.

Blitz, Hans-Martin. Aus Liebe zum Vaterland: Die Deutsche Nation im 18. Jahrhundert, 2000.

Borneman, John. Belonging in the Two Berlins: Kin, State, Nation, 1992.

Brubaker, Rogers. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany, 1992.

Buse, Dieter K., and Jürgen Dörr. Modern Germany: An Encyclopedia of History, People, and Culture, 1871– 1990, 1998.

Chickering, Roger. We Men Who Feel Most German: A Cultural Study of the Pan-German League, 1886–1914, 1984.

Craig, Gordon A. Germany, 1866–1945, 1978.

——. The Germans, 1991.

Dann, Otto. Nation und Nationalismus in Deutschland, 1770–1990, 1993.

Elias, Norbert. The Germans: Power Struggles and the Development of Habitus in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.

——. The Civilizing Process, Rev. Ed., 2000.

Forsythe, Diana. "German Identity and the Problem of History." In E. Tonkin, M. McDonald, and M. Chapman, eds., History and Ethnicity, 1989.

Francois, Etienne, and Hannes Siegrist, eds. Nation und Emotion: Deutschland und Frankreich im Vergleich im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, 1995.

Hermand, Jost. Old Dreams of a New Reich: Völkisch Utopias and National Socialism, 1992.

Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, eds. The Invention of Tradition, 1984.

Iggers, Georg G. The German Conception of History: The National Tradition of Historical Thought from Herder to the Present, Rev. Ed., 1983.

Koonz, Claudia. Mothers in the Fatherland, 1987.

Lowie, Robert H. Toward Understanding Germany, 1954.

Maier, Charles. The Unmasterable Past: History, Holocaust, and German National Identity, 1988.

Merkel, Ina. Utopie und Bedürfnis: Die Geschichte der Konsumkultur in der DDR, 1999.

Mosse, George L. The Nationalization of the Masses: Political Symbolism and Mass Movements in Germany from the Napoleonic Wars through the Third Reich, 1975.

Nipperdey, Thomas. Germany from Napoleon to Bismarck, 1996.

Peukert, Detlev J. Inside Nazi Germany: Conformity, Opposition, and Racism in Everyday Life, 1989.

Schulze, Gerhard. Die Erlebnisgesellschaft: Kultursoziologie der Gegenwart, 4th ed., 1993.

Sheehan, James J. German History, 1770–1866, 1989.

Siegrist, Hannes. "From Divergence to Convergence: The Divided German Middle Class, 1945–2000." In O. Zunz, ed., Social Contracts Under Stress, 2001.

Tacitus, Cornelius. Agricola; and Germany, 1999.

Ten Dyke, Elizabeth. "Memory, History and Remembrance Work in Dresden." In D. Berdahl, M. Bunzl, and M. Lampland, eds., Altering States: Ethnographies of Transition in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, 1999.

Tipton, Frank B. Regional Variations in the Economic Development of Germany During the Nineteenth Century, 1976.

Walker, Mack. German Home Towns, 1971.

—J OHN E IDSON

source: everyculture.com/

.jpg)